What is Coronavirus

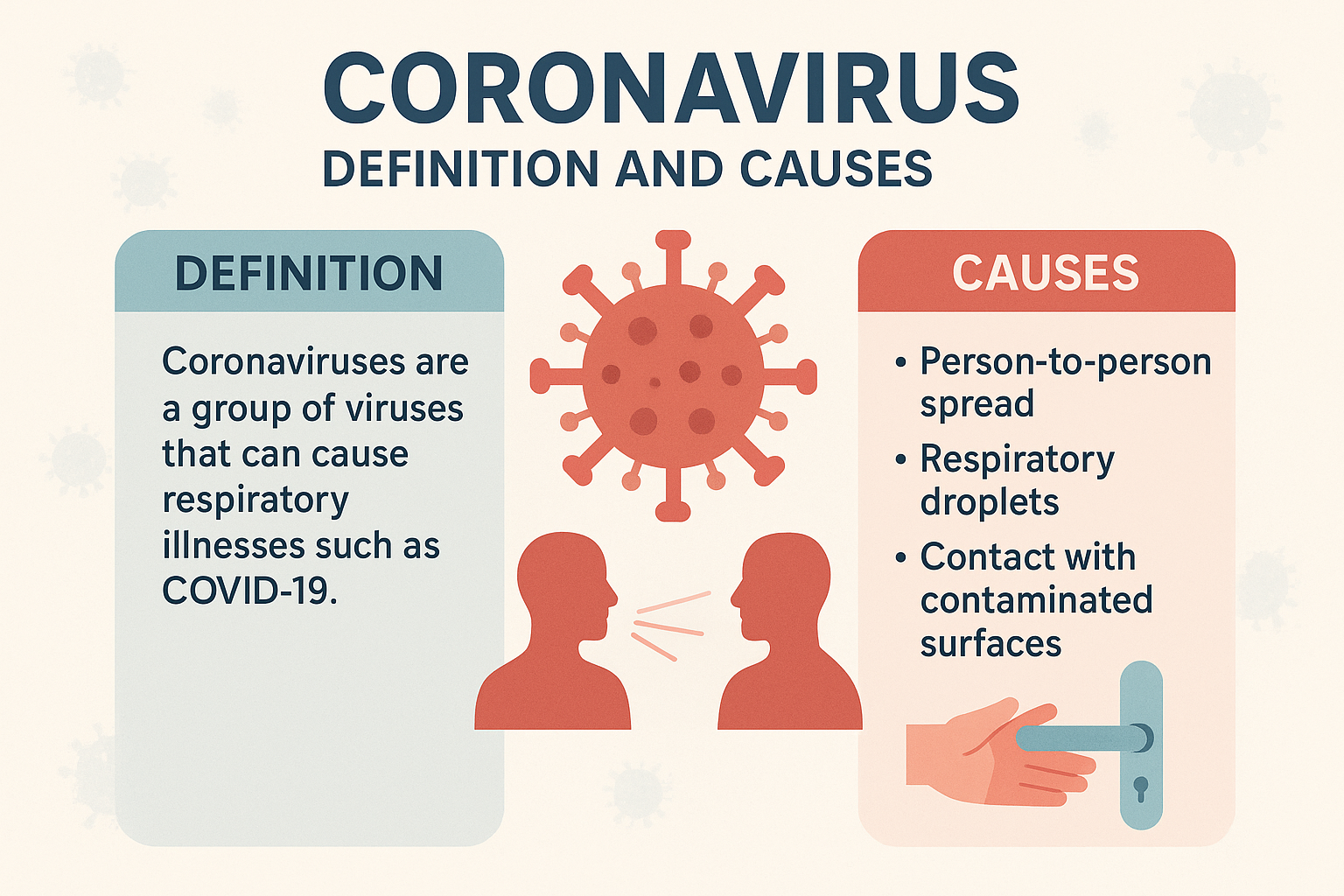

Coronavirus refers to a large family of viruses that can cause illnesses in both humans and animals. In humans, these viruses are known to affect primarily the respiratory system, leading to diseases that range from mild infections like the common cold to severe respiratory syndromes such as SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome), MERS (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome), and COVID-19.

The term “corona” comes from the Latin word meaning “crown” or “halo.” Under a microscope, the virus appears to have crown-like spikes on its surface — these are spike (S) proteins that allow the virus to attach to and enter human cells. This structure is one of the main reasons the virus can spread so effectively.

Coronaviruses are RNA viruses, meaning their genetic material is made of ribonucleic acid rather than DNA. This allows them to mutate more quickly, leading to the emergence of new variants over time. The virus spreads mainly through respiratory droplets released when an infected person coughs, sneezes, or talks. It can also spread by touching contaminated surfaces and then touching the mouth, nose, or eyes.

The most notable strain, SARS-CoV-2, is the virus responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic, first identified in Wuhan, China, in late 2019. It rapidly spread worldwide, causing a global health emergency. Symptoms range from mild fever and cough to severe pneumonia, respiratory distress, and in some cases, death.

In summary, coronavirus is a highly contagious viral agent capable of causing a wide spectrum of respiratory illnesses. Its discovery and the global pandemic it caused have reshaped healthcare systems and public health practices worldwide, emphasizing the importance of hygiene, vaccination, and preparedness for future outbreaks.

Structure and Nature of the Coronavirus

The coronavirus is a microscopic, spherical virus with a distinctive appearance that sets it apart from many other pathogens. Its structure plays a vital role in how it infects human cells and causes disease. The outer surface of the virus is covered with spike-shaped proteins, giving it a crown-like appearance—hence the name “corona.” These spikes are essential because they enable the virus to attach to receptors on human cells, particularly the ACE2 receptors found in the lungs and other organs.

At its core, the coronavirus contains a single strand of RNA, which serves as its genetic material. Unlike DNA viruses, RNA viruses can mutate quickly, which is why new variants of coronavirus continue to emerge. This RNA is enclosed within a protective protein shell called the nucleocapsid, which helps stabilize and protect the viral genome. Surrounding this core is a lipid envelope, a fatty layer that helps the virus survive and merge with host cells. However, this lipid coating is also fragile—soap and disinfectants can easily break it down, which is why handwashing is such an effective preventive measure.

The main structural components of coronavirus include:

- Spike (S) protein: responsible for binding to host cell receptors and enabling viral entry.

- Envelope (E) protein and Membrane (M) protein: essential for the virus’s shape and assembly.

- Nucleocapsid (N) protein: binds to the RNA genome to form the inner structure of the virus.

The unique combination of these proteins and the viral envelope gives coronavirus its strong infectious potential. Its ability to adapt, survive, and mutate makes it a persistent challenge for scientists and healthcare professionals. Understanding this structure is key to developing effective treatments, vaccines, and diagnostic methods.

Types of Coronaviruses

Coronaviruses form a large family of viruses that affect both animals and humans. Among them, several strains are known to infect humans and cause respiratory illnesses of varying severity. These viruses are classified into four main groups: alpha, beta, gamma, and delta coronaviruses. Of these, alpha and beta coronaviruses are primarily responsible for human infections.

Before the emergence of COVID-19, human coronaviruses were mainly associated with mild respiratory illnesses such as the common cold. The early known strains include HCoV-229E, HCoV-NL63, HCoV-OC43, and HCoV-HKU1. These viruses typically cause mild symptoms like cough, sore throat, and fever, and are rarely linked to severe disease. However, in the past two decades, new and more dangerous strains have emerged that cause serious outbreaks and high mortality rates.

The major types of coronaviruses that have significantly impacted human health are:

1. SARS-CoV (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus):

First identified in 2002 in China, SARS-CoV caused a global outbreak with severe respiratory symptoms and a high fatality rate. Although it was eventually contained, it revealed how quickly coronaviruses could spread and evolve.

2. MERS-CoV (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus):

Detected in 2012 in Saudi Arabia, MERS-CoV is believed to have originated from camels and caused severe respiratory illness. Its spread was more limited compared to SARS, but it had a higher mortality rate.

3. SARS-CoV-2 (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2):

This is the virus responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic that began in late 2019. It shares genetic similarities with SARS-CoV but spreads much more easily from person to person. SARS-CoV-2 has caused millions of infections and deaths worldwide, leading to unprecedented global health, social, and economic challenges.

Each of these coronaviruses demonstrates the ability of viral pathogens to jump from animals to humans—a process known as zoonotic transmission. This highlights the importance of monitoring animal populations and maintaining global surveillance systems to detect potential outbreaks early.

Origin and Spread of COVID-19

The origin of COVID-19 traces back to Wuhan, China, in December 2019, where several cases of unexplained pneumonia were reported. Investigations revealed a new strain of coronavirus—later named SARS-CoV-2—as the cause of the outbreak. The initial cluster of cases was linked to a seafood and live animal market, suggesting a zoonotic origin, meaning the virus likely jumped from animals to humans.

Once the virus adapted to human transmission, it spread with extraordinary speed. Within weeks, it had moved beyond Wuhan, across China, and to other countries through international travel. By March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a global pandemic—the first of its kind in over a century.

The spread of COVID-19 was primarily driven by person-to-person transmission through respiratory droplets expelled when an infected person coughed, sneezed, or talked. The virus could also survive for a limited time on contaminated surfaces, allowing indirect transmission. As the infection spread silently—often through asymptomatic carriers—traditional containment methods like contact tracing and isolation became increasingly difficult.

Global mobility and densely populated cities further accelerated the spread. Major international hubs became centers of transmission, turning what began as a localized outbreak into a worldwide health crisis. Governments implemented drastic measures such as lockdowns, travel bans, and quarantine protocols to slow the infection rate. Despite these efforts, the virus’s ability to mutate led to multiple waves of infection, each posing new challenges.

By the time vaccines were developed and distributed in 2021, millions of lives had been lost, and nearly every nation had been affected. The pandemic revealed how interconnected and vulnerable modern societies are, emphasizing the importance of public health infrastructure, early detection systems, and global cooperation in preventing future outbreaks.

Mode of Transmission

The mode of transmission of coronavirus is central to understanding how COVID-19 spread so rapidly across the world. The virus primarily transmits from one person to another through respiratory droplets released when an infected individual coughs, sneezes, talks, or even breathes. These droplets contain viral particles that can enter the body of another person through the mouth, nose, or eyes, especially when standing close to the infected individual.

In addition to large droplets, scientific evidence has shown that smaller aerosol particles can remain suspended in the air for longer periods, particularly in closed or poorly ventilated spaces. This means that even without direct physical contact, people in crowded indoor settings can inhale these aerosols and become infected. Such airborne transmission is one reason COVID-19 spread easily in places like offices, public transport, and social gatherings.

Another possible route is surface or fomite transmission, where a person touches a contaminated surface—such as doorknobs, phones, or tables—and then touches their face. Although this mode is less common compared to airborne spread, it reinforces the importance of hand hygiene and regular disinfection of frequently touched objects.

Asymptomatic transmission further complicated containment efforts. Individuals who showed no symptoms of infection were still capable of spreading the virus, unknowingly transmitting it to others. This silent spread made early detection and isolation difficult, contributing to the rapid global expansion of COVID-19.

Environmental factors also influence transmission. Enclosed areas with limited air circulation, lack of sunlight, and high humidity can enhance viral persistence in the air and on surfaces. On the other hand, outdoor environments with proper ventilation reduce the risk significantly.

Understanding these transmission routes guided global public health strategies—mask wearing, social distancing, improving ventilation, and regular handwashing became essential preventive measures. Each of these actions directly targets one or more modes of viral spread.

In summary, the coronavirus spreads mainly through respiratory droplets, aerosols, and close contact, with surface transmission playing a minor role. This knowledge remains vital not only for controlling COVID-19 but also for preparing against future respiratory viral outbreaks.

Symptoms of Coronavirus Infection

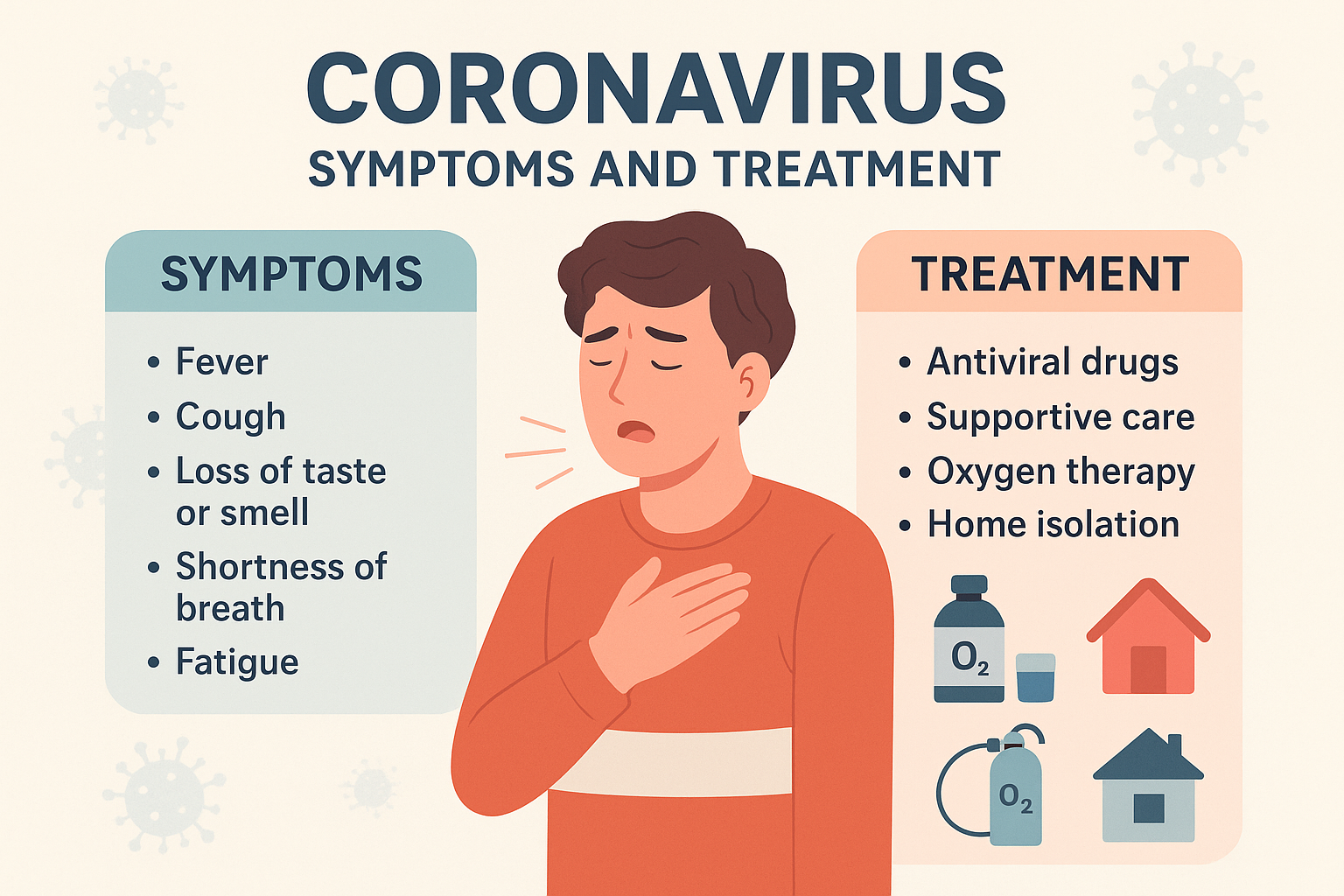

The symptoms of coronavirus (COVID-19) vary widely from person to person, ranging from completely asymptomatic cases to severe respiratory distress requiring hospitalization.

In most cases, the infection begins with mild, flu-like symptoms that appear within 2 to 14 days after exposure to the virus. The most common early signs include fever, dry cough, sore throat, fatigue, and body aches. Some individuals experience headache, nasal congestion, or a runny nose, which makes the infection difficult to distinguish from seasonal influenza or common cold in its early stages.

One of the hallmark features of COVID-19 is the loss of taste (ageusia) and loss of smell (anosmia), which became key indicators of infection during the pandemic. These sensory changes can occur even in the absence of fever or respiratory symptoms and may persist long after recovery.

As the infection progresses, some individuals develop shortness of breath, chest pain, or difficulty breathing, indicating lower respiratory tract involvement. In severe cases, this may lead to pneumonia or acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)—a life-threatening condition requiring oxygen therapy or mechanical ventilation.

Gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea have also been observed, particularly in children and some adults. Elderly people and those with pre-existing health conditions like diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, or chronic lung disorders tend to experience more severe symptoms and complications.

Many patients recover within two to three weeks, but some continue to experience lingering health issues—a condition known as “long COVID.” Symptoms like fatigue, muscle weakness, difficulty concentrating, and breathlessness may persist for weeks or months after the infection has cleared, affecting quality of life and daily functioning.

Overall, coronavirus symptoms affect multiple organ systems, not just the lungs. This wide range of clinical manifestations—from mild fever to multi-organ failure—reflects the virus’s ability to impact the respiratory, circulatory, and nervous systems simultaneously.

Recognizing these symptoms early and seeking medical attention when necessary remains essential. Timely testing, isolation, and supportive care can significantly reduce the risk of severe illness and prevent further spread within the community.

Diagnosis of COVID-19

The diagnosis of COVID-19 involves a combination of clinical evaluation, laboratory testing, and imaging studies to confirm the presence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in the body.

The most reliable and widely used diagnostic test is the RT-PCR (Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction) test. This test detects the virus’s genetic material (RNA) from a sample collected through a nasal or throat swab. Because of its high sensitivity and specificity, RT-PCR became the global standard for confirming COVID-19 infection. However, it requires laboratory processing and trained personnel, which can delay results in large-scale outbreaks.

For quicker results, rapid antigen tests were developed. These tests detect viral proteins on the surface of SARS-CoV-2 using a swab sample, and results are typically available within 15 to 30 minutes. Although less sensitive than RT-PCR, antigen tests proved valuable for mass screening, especially in community settings and airports.

In some cases, chest imaging—such as X-rays or CT scans—is used to assess the extent of lung involvement, especially in patients with breathing difficulties. Characteristic findings, like ground-glass opacities in the lungs, help doctors evaluate disease severity and monitor progression even before laboratory results are confirmed.

Serological or antibody tests are another category of diagnostic tools. These tests detect antibodies produced by the immune system in response to infection, helping determine if a person was previously exposed to the virus. However, they are not used for diagnosing active infection since antibodies take time to develop after exposure.

Along with testing, clinical symptoms and exposure history also play a key role in diagnosis. Health professionals consider factors such as recent contact with confirmed cases, travel history, and the presence of typical symptoms like fever, cough, and loss of smell.

In hospital settings, additional laboratory markers—like C-reactive protein (CRP), D-dimer, and oxygen saturation levels—are often evaluated to determine the severity of infection and the need for intensive care.

In summary, the diagnosis of COVID-19 relies on a layered approach: RT-PCR for confirmation, rapid tests for screening, imaging for assessment, and antibody tests for past exposure.

Complications and Risk Factors

While many people infected with the coronavirus (COVID-19) experience only mild or moderate symptoms, some develop serious complications that can be life-threatening. These complications arise when the virus triggers an excessive immune response or affects multiple organs beyond the respiratory system. The severity of illness largely depends on the person’s age, general health, and the presence of pre-existing medical conditions.

The most common and severe complication is pneumonia, in which the lungs become inflamed and filled with fluid, making breathing difficult. In critical cases, pneumonia can progress to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)—a condition where the lungs fail to supply enough oxygen to the body. ARDS often requires oxygen therapy, mechanical ventilation, or intensive care management.

COVID-19 can also lead to multi-organ damage. The virus affects not only the lungs but also the heart, kidneys, liver, and brain. Some patients experience myocarditis (inflammation of the heart muscle), irregular heart rhythms, or heart failure, even without prior heart disease. Similarly, acute kidney injury has been observed in severe cases, often requiring dialysis support.

The virus can also cause blood clotting disorders, leading to stroke, pulmonary embolism, or deep vein thrombosis (DVT). This occurs because the infection triggers abnormal activation of the body’s clotting system. Such complications increase the risk of death, particularly in hospitalized or critically ill patients.

Another concern is the cytokine storm, a dangerous immune overreaction where the body releases excessive inflammatory substances in an attempt to fight the virus. Instead of helping recovery, this response damages tissues and organs, worsening the patient’s condition.

Certain groups face a significantly higher risk of developing these complications. Older adults, especially those over 60 years of age, are more vulnerable due to weakened immunity. People with chronic diseases—such as diabetes, hypertension, obesity, chronic lung disease, or cardiovascular conditions—are also more likely to experience severe illness. Similarly, individuals with compromised immune systems, including cancer patients or those on immunosuppressive therapy, have reduced ability to fight infection.

Even after recovery, some individuals suffer from post-COVID complications such as fatigue, shortness of breath, brain fog, and muscle weakness. This condition, often referred to as “long COVID,” can persist for weeks or months and may affect quality of life and work capacity.

Treatment and Management

The treatment and management of coronavirus (COVID-19) depend on the severity of the infection, the symptoms present, and the individual’s overall health condition. While there is no single cure that eliminates the virus completely, a combination of medical care, supportive therapy, and preventive strategies has proven effective in reducing complications and improving recovery rates.

For most individuals with mild or moderate symptoms, treatment focuses on symptomatic relief and home care. Patients are advised to rest, stay hydrated, and monitor their temperature and oxygen levels regularly. Medications such as paracetamol (acetaminophen) are used to manage fever and body pain, while adequate nutrition and isolation help prevent transmission to others. Medical supervision through teleconsultation ensures early detection of any worsening symptoms.

In cases of moderate to severe infection, hospitalization may be required. The primary goal of hospital treatment is to maintain adequate oxygenation and support vital functions. Oxygen therapy is often administered to patients with low oxygen saturation, while those experiencing respiratory distress may need mechanical ventilation or non-invasive respiratory support.

Doctors also use antiviral medications such as remdesivir in specific cases to reduce viral replication, although their effectiveness varies depending on the stage of infection. Corticosteroids like dexamethasone are used to control inflammation in patients with severe respiratory symptoms, helping reduce lung injury caused by the body’s immune response.

For patients at high risk of complications, anticoagulants are prescribed to prevent blood clots, which are a common and dangerous outcome of severe COVID-19. Antibiotics, however, are only used when bacterial infections occur alongside the viral illness, as COVID-19 itself is caused by a virus and does not respond to antibiotic treatment.

Supportive care also includes managing dehydration through intravenous fluids, maintaining electrolyte balance, and monitoring organ function closely. In critical cases, intensive care units (ICUs) provide advanced life support, including mechanical ventilation, dialysis for kidney failure, or even extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) when conventional methods are insufficient.

After the acute phase of illness, rehabilitation and post-COVID management become essential. Patients recovering from severe infection often experience lingering fatigue, breathlessness, and muscle weakness. Pulmonary rehabilitation, physical therapy, and gradual return to activity help restore lung function and overall health.

Mental health support also forms an important part of COVID-19 management, as prolonged illness and isolation can lead to anxiety, depression, or sleep disturbances. Counseling, family support, and stress-relief techniques aid in emotional recovery.

In conclusion, the treatment and management of coronavirus require a comprehensive and individualized approach. From home-based care for mild cases to advanced hospital treatment for severe illness, every level of intervention aims to reduce complications, save lives, and support long-term recovery. Continued medical research and improved access to healthcare have strengthened the world’s ability to manage COVID-19 effectively, transforming it from a deadly pandemic to a controllable infectious disease.

COVID-19 Vaccination

Vaccination stands as the most powerful and effective tool in controlling the COVID-19 pandemic. It has transformed the global response from crisis management to prevention, significantly reducing hospitalizations, severe illness, and death. COVID-19 vaccines work by training the body’s immune system to recognize and fight the SARS-CoV-2 virus without causing the disease itself.

The development of vaccines against coronavirus was a historic scientific achievement. Within a year of identifying the virus, researchers around the world created multiple safe and effective vaccines through advanced technologies and global cooperation. These vaccines target the spike protein on the virus’s surface — the same structure it uses to enter human cells. By producing antibodies against this protein, the immune system can quickly respond if exposed to the actual virus in the future.

There are several types of COVID-19 vaccines, each using a different method to trigger immune protection:

- mRNA vaccines (Pfizer-BioNTech, Moderna): These vaccines use a small piece of the virus’s genetic code to instruct the body to produce the spike protein temporarily, stimulating an immune response.

- Vector-based vaccines (AstraZeneca, Johnson & Johnson, Sputnik V): These use a harmless virus to deliver genetic material from SARS-CoV-2 into cells, prompting the immune system to build defense.

- Inactivated vaccines (Covaxin, Sinopharm, Sinovac): These contain virus particles that have been killed or weakened, enabling the immune system to recognize them without risk of infection.

- Protein subunit vaccines (Novavax): These use purified pieces of the virus (like the spike protein) to provoke an immune response directly.

Each of these vaccines has been tested extensively for safety, efficacy, and side effects before approval by health authorities such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and national regulatory agencies. While mild side effects such as soreness, fatigue, or fever may occur, they are temporary and indicate the body’s immune system is responding appropriately.

A complete vaccination schedule, often requiring two doses followed by a booster, provides stronger and longer-lasting protection. Boosters became especially important as new variants of the virus emerged, some with mutations that allowed partial escape from immune detection. Updated booster doses were designed to enhance immunity against these variants and maintain population-level protection.

Beyond individual protection, vaccination contributes to herd immunity, reducing overall transmission within communities and protecting those unable to receive vaccines due to medical conditions. It also helped restore global stability—allowing schools, workplaces, and travel to resume safely.

Public health campaigns played a key role in spreading awareness, addressing misinformation, and ensuring equitable vaccine distribution. The success of mass vaccination drives in many countries demonstrated the power of science, collaboration, and public responsibility.

In summary, COVID-19 vaccination not only saved millions of lives but also changed the future of infectious disease prevention. It proved that with rapid scientific innovation, global coordination, and public participation, humanity can effectively respond to even the most challenging pandemics. Vaccines remain the cornerstone of long-term protection against coronavirus and a critical defense for any future outbreaks.